A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A CHEMICAL MANAGEMENT OFFICER, DEALING WITH BODILY FLUIDS AND CAUSTIC SPILLS

Everything changes for Chris Giglio when his phone beeps. It’s a page from the Colorado State University Police Department and there is blood in a bathroom on campus. He calls dispatch to learn more, and although there’s not much information about the situation — it’s unclear how this happened — he gets the details he needs. It’s a small spill, and he needs to go clean it up.

Giglio had driven into work at dawn on a snowy Tuesday morning in khaki pants, a black hoodie, and an orange ball cap. Before the page on his phone, his morning was free of meetings and he hoped to catch up on the paperwork piling up on his desk. Instead he walks into his office as intended but only stays for a few minutes. He doesn’t even sit down at his desk. From the corner, he grabs a bucket containing latex gloves, safety glasses, and a cleaning product that has a fast contact time and kills a wide variety of agents. He also takes a dust mask and lab coat, in case the situation happens to be more serious than expected, and he considers colleagues he’ll call to help, if necessary.

When he gets to the bathroom and views the spill he sees it’s something he can handle alone. He’s been trained for this. He initiates a procedure he knows well, starting with putting on his protective gear. Then he begins at the outside of the spill and moves inward, wetting the blood with the cleaning agent and allowing it to sit for several minutes so it can do its job of destroying live cells.

And then half an hour later, voila — the blood is gone and the bathroom is clean and safe for people to use again. He throws the soiled clothes in the trash, and on his way out, he removes the “Do Not Enter” sign blocking the door.

This is a day in the life of a Chemical Management Officer and emergency response professional, housed on a campus of about 30,000 students and 1,700 faculty members.

But it’s only one day, and one incident. Giglio’s job, which resides within the Environmental Health Services department, involves dozens of different types of scenarios. As Murphy’s Law would have it, they sometimes occur in the middle of the night, or on major holidays.

“A university is a little city within a city,” says Giglio. “So there are so many things that can happen, at any time.”

“WE JUST FOUND SOMETHING UNDER THE SINK. IT DOESN’T LOOK GOOD. CAN YOU COME AND SEE WHAT IT IS?”

Giglio has a long list of examples. For starters, he and his colleagues recently helped respond to a break-in on campus, where the perpetrator shattered a plate glass window and spurted blood on the floor. He’s also dealt with minor explosions, one which involved both chemical and blood clean-up. Once, he had to remove inactive ricin from a microbiology lab.

And about three years ago, there was a major fire in the Equine Reproduction Laboratory, resulting in the building burning to the ground. A few days after the fire, when the facility was released back to the university, Giglio and his colleagues spent a few days cleaning up chemicals spanning the full spectrum of “hazardous,” from gas cylinders to anesthetics. They also had to secure a controlled substance box and clean up burned refrigerators and janitorial closets.

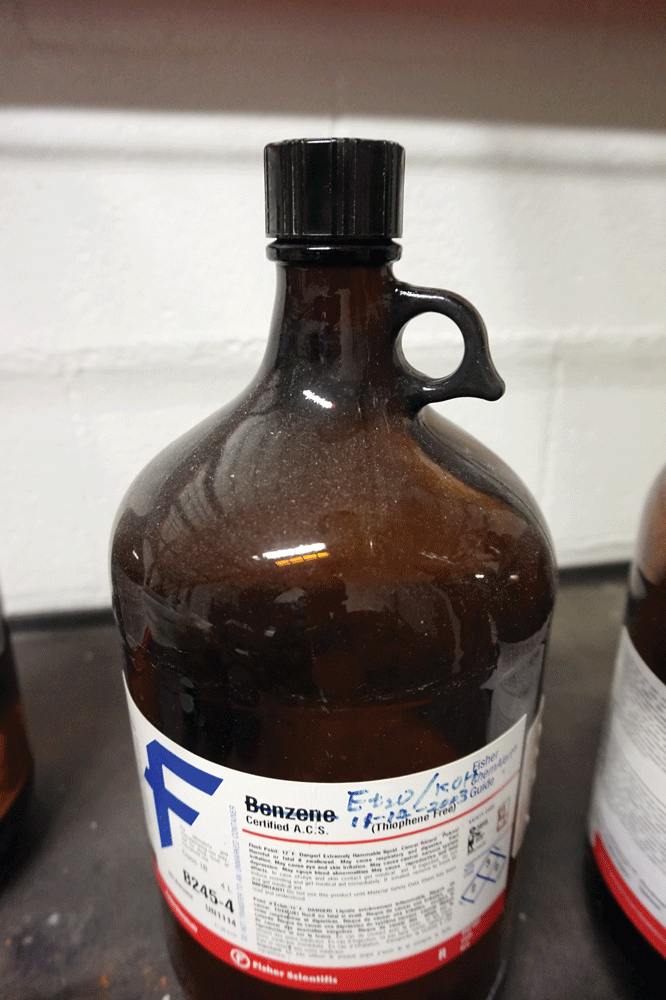

Because the school is a Carnegie Research University, there’s a high amount of research activity (read: lots of chemicals) involving everything from snake venom to peroxides. One of Giglio’s major tasks, which spanned almost six months in 2014, involved completing a total inventory of the chemicals on campus. Brought on by Department of Homeland Security regulations, Giglio and his team worked diligently to bar code all the chemicals used at the university. They instituted an amnesty period as part of this initiative. Giglio told people to “bring me your old chemicals. Box them up, call them amnesty, and email me with where they are.” Then he went and picked everything up in his white work pick-up truck, and he turned to focusing on how best to dispose of them.

In a couple of situations, people found unknown chemicals in a dusty corner, and the bottles had crystals on them, which meant they could be explosive. They called Giglio saying, “We just found something under the sink. It doesn’t look good. Can you come and see what it is?” In these types of cases, where danger was potentially high, Giglio puts on his “explosive team” hat. He has expertise in this area, and he works closely with a bomb tech who’s been highly trained, including through an FBI program. Giglio describes himself as “the chemist part of the partnership.” The bomb tech designed the charge and together they got rid of the explosive component.

“We hand-carried the bottles out to a vacant lot, with a special permit, and detonated them,” he says. But with most unknown chemicals, detonation isn’t necessary, Giglio and his team bring them to their facility and sample them using a Hazardous Categorization Kit (Haz- Cat Kit), which is basically a big chemistry box and includes a chart they follow in order to identify the constituents. Then they put the chemical into a category.

“We look for corrosivity, reactivity, and toxicity,” says Giglio. Once the chemical has a category, they often bulk it up, which means transferring it into a large drum under protective hoods, in order to prepare it for hazardous waste disposal. Sometimes this means an incineration facility. Other times, it’s more complicated. In this case, the chemicals get held in various “cells” — rooms with locked doors, separated by category — until Giglio determines the best options for disposal.

At the end of the day (which never actually ends) Giglio feels good about his work, and he believes he’ll stay with it for many more years. “I love the problem solving and variety,” says Giglio.

USE THESE TIPS TO STAY SAFE

If you come across a bottle of chemicals, maybe shoved back under the kitchen sink, or in a corner of your shed, Chris Giglio offers the following tips for handling the situation safely.

- Do not touch the bottle.

- Put on protective gear, which includes safety goggles and latex gloves.

- Go up to the bottle. Can you identify the chemical? If there’s a label on the bottle, can you read it?

- If yes, look the chemical up online. For example, if you find brake fluid, many communities have household hazardous material pick-ups a few times a year (or drop-off days), so see if this exists in your community.

- If no, get a picture of it and send it to your local municipality or health department. Ask them for advice on disposal.

Things to keep in mind:

- What material is the bottle made of? Plastic, metal, glass? If it’s plastic, remember it can get brittle over time and may disintegrate if you touch it.

- Is there corrosion or crystals on the outside of the bottle? Chemicals left in sunlight can produce peroxides (crystals) in the container, which can be explosive. If you find something like this, don’t go near it. Call for help.

Editors Note: A version of this article first appeared in the June 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.