The power has been out for 38 days, and what looked like a short-term blackout has now turned into a serious event. Fire and police departments have been largely overwhelmed, and the 911 system has been down for weeks.

Roving bands of gangs now regularly walk the streets, and it is dangerous to leave your house. Your neighbor shows up at your door with a blood-soaked t-shirt wrapped around his wrist. He is confused, pale, sweaty, and breathing rapidly. As he collapses in your doorway, you see that his hand is completely severed at his wrist.

You’re in the “Golden Hour”—and you are on your own.

The “Golden Hour” was first described by R. Adams Cowley, M.D., at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore. From his personal experiences and observations in post-World War II Europe and then in Baltimore in the 1960s, Dr. Cowley recognized that the sooner trauma patients reached definitive care—particularly if they arrived within 60 minutes of being injured—the better their chances of survival.

The following traumatic injuries are some of the more common types of trauma you might find yourself facing in a survival situation when the EMS system is not intact. On your own, you must fix what you can while your patient is still in the “Golden Hour.”

Disinfection can be accomplished with the following methods:

- Wash and boil soiled linen or bandage items for five minutes.

- Alternatively, wash, rinse, and soak items for 30 minutes in a 0.1% chlorine solution or 5% Lysol solution

- Iron items on a table covered with a drape that has also been ironed. Dampen each item with boiled water. The iron should be hot and several passes made.

- Hang in full sunlight for six hours per side.

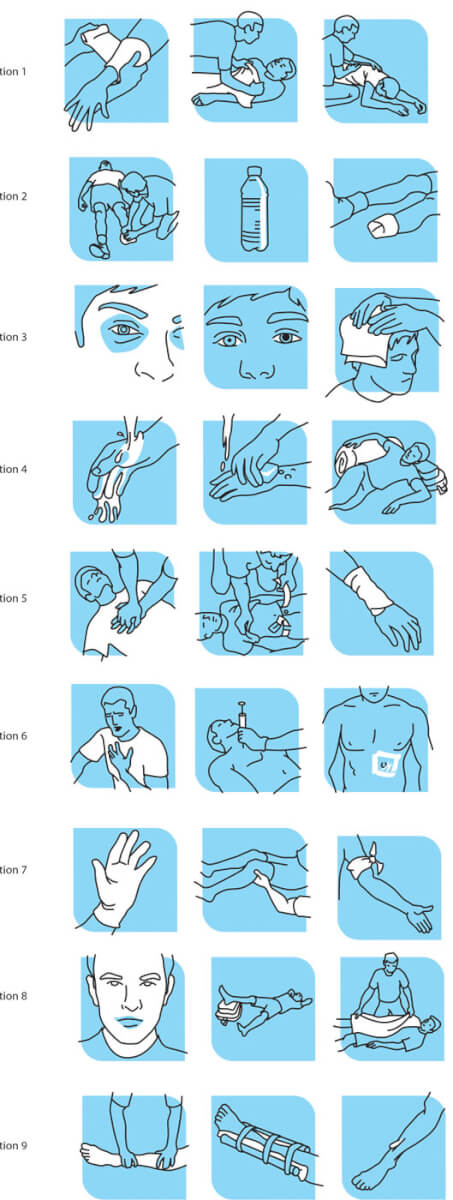

1. Gun Shot Trauma

If you have taken any type of first aid training, you are familiar with the term, “ABC”—Airway-Breathing-Circulation. If you find yourself treating the victim of a gunshot wound in a survival situation without EMS services, your first priority is addressing circulation.

How to treat:

- Stop the bleeding. Direct pressure, elevation, and a pressure bandage (in that order) usually work for most extremities. The Israeli Emergency Bandage or Olaes Modular Bandage would be good choices if one is available. You can improvise with a towel, bandana or shemagh. This is a headcloth designed for a desert environment to protect the wearer from sand and heat). If direct pressure does not stop the bleeding, a hemostatic agent such as Quick Clot or Celox can be applied with direct pressure.

- Treat for shock. You should be doing this as you’re doing the other steps. Cover the victim for warmth. Keep them covered unless there’s a reason not to, such as if you are checking for wounds.

- Look over the entire body for wounds. You can’t just depend on looking for entry and exit wounds, thinking you know where the bullet has traveled. Sometimes, the bullet can hit a bone, break into fragments, and stray anywhere in the body. In fact, some types of bullets are designed to cause multiple injuries.

For a gunshot wound in the arms or legs, consider bones.

How to treat:

- Direct pressure, elevation, and pressure bandage—in that order. Elevate the wound above the heart, and apply a pressure bandage. If it’s still bleeding, take your fingers and apply pressure to the brachial artery for the arm or the femoral artery for the leg.

- If all else fails in an extremity, go to a tourniquet. It may come down to “lose a limb or lose a life.”

- If the area is rapidly swelling, that’s a sign of internal bleeding. Also, consider that a bone might have been injured or even shattered. If you suspect this, the area needs to be splinted.

- The objective of emergency tourniquet use is to extinguish the distal (that is, a location situated away from the center of the body or from the point of attachment) pulse, thereby controlling bleeding distal to the site of tourniquet application.

- Tourniquets provide maximal benefit the earlier they are applied following difficult-to-control extremity hemorrhage.

- Improvised (windlass) tourniquets should be applied only when scientifically designed tourniquets are absent. A windlass is a lever that can be wound to tighten a tourniquet.

- Tourniquets work better when applied distally (forearms and calves) than when applied more proximally (upper arms or thighs).

- Remove clothing and other underlying materials prior to tourniquet application (when possible) to ensure a tight and secure tourniquet fit.

- Remove the clothing surrounding a tourniquet to enable identification of all surrounding wounds and injuries.

- Do not apply tourniquets directly over joints, because compression of vascular structures and bleeding control are limited by overlying bone.

- If one tourniquet is ineffective, side-by-side (in sequence longitudinally), dual tourniquet use might be effective.

- Mark the time the tourniquet was applied with a permanent marker and in plain sight.

For a gunshot wound in the abdomen, consider organ protection.

How to treat:

- If the wound is open and you can see the intestines, find a moist, sterile dressing to place on top of the wound (to protect the organs). If the intestines are ripped open and the victim does not get immediate medical care, they will likely bleed to death or die from the severe infection that will probably ensue.

- The victim should take nothing at all by mouth until the pain lets up and then wait a day or two. This is obviously a difficult situation, but this step is very important and is a time when a slow drip of IV fluids would be useful.

For a gunshot wound in the chest, consider air sucking and spine injury.

How to treat:

- Open chest wounds are also called “sucking chest wounds,”because they suck air in and can lead to a collapsed lung. You can help stop the sucking by closing the open wound with an occlusive dressing. Improvise with a plastic bag taped on three sides if you do not have access to a commercially produced chest seal.

- Remember that the spine is also included in the back of the chest. Be very careful about movement of chest wound victims. Keep them as still as possible in order to avoid damaging the spinal cord. If the heart, lungs, spine, or a large blood vessel is damaged, there’s not much you can do in a survival situation if immediate expert medical care is unavailable.

- In most circumstances, don’t remove an implanted bullet. It’s almost impossible to find, and it might actually be plugging a big blood vessel. (Thousands of military members live daily with shrapnel in their bodies.) Unless there’s initial infection from the wound, itself, the body adapts to most metal without many serious problems.

2. Traumatic Amputation

Treatment provided for a patient who has suffered an amputation is influenced by numerous factors. Management of potentially life-threatening conditions is the first priority. Management of victims of amputations from blunt trauma is complicated by the concern about additional injuries. Blunt trauma amputations are often caused by mechanisms of high-energy transfer, such as collapsed buildings after an earthquake, auto or industrial accidents, or debris from a tornado.

These accidents often involve the potential for multisystem trauma, and you must stay alert to the possibility of other injuries. It is critical to remember that the most obvious injury is not always the most significant. Partial amputations should be assessed and treated as if they are fully intact.

If there is complete amputation and the anatomy is retrieved, without an intact EMS system, there is no chance the limb will be able to be saved for possible re-attachment.

How to treat:

- The first priority is to control major bleeding immediately through direct pressure and elevation. Tourniquets can be used when pressure and elevation fail. Place the tourniquet as close to the amputation site as possible.

- The next priority is to maintain and support essential life functions. Supportive measures such as airway control and body temperature can slow the onset of life-threatening shock. Using a 60cc to 100cc irrigation syringe, flush the area aggressively with a diluted solution of Betadine (povidone-iodine) or sterilized saline solution. If you don’t have commercial sterile solutions, studies show that clean drinking water can keep a wound clean in an austere environment.

- Dressings such as a saline-moistened sterile dressing placed over exposed tissue will help to reduce additional contamination or injury. Cover with a dry, sterile gauze dressing. Replace the dressing at least daily; more often, if possible.

- If an extremity is involved, it should be splinted.

3. Head Trauma/Concussion/Skull Fracture

Head injuries can be divided into three groups:

- Prolonged unconsciousness (more than five to 10 minutes)

- Brief loss of consciousness

- No loss of consciousness

Prolonged unconsciousness: Loss of consciousness for more than five to 10 minutes is a sign of significant brain injury. Assess the victim’s airway and perform rescue breathing if necessary. Because there is a potential for accompanying neck and spine injuries with severe head trauma, the victim’s spine should be immobilized.

In a survival situation, you will obviously be unable to immediately evacuate the victim to a medical facility. Your only course of action at this point is to maintain spine immobilization and keep the victim’s head pointed uphill. Be prepared to logroll the victim onto their side if they vomit. Continually monitor the airway for signs of obstruction (listen for noisy or labored breathing) and a decreasing respiratory rate.

Brief loss of consciousness: Short-term unconsciousness, in which the victim wakes after a minute or two and gradually regains normal mental status and physical abilities, is evidence of a concussion. A concussion does not usually produce permanent damage, although confusion or amnesia about the event and repetitive questioning by the victim are common.

At a minimum, you should keep the victim under close observation for at least 24 hours and not allow them to perform potentially hazardous activities. Normal sleep should be interrupted every three to four hours to check briefly that the victim’s condition has not deteriorated and that they can be easily roused. If the victim becomes increasingly lethargic, confused, combative, is just not acting their normally, or if they develop any other signs (see these under “No Loss of Consciousness,” below), your only option without an intact EMS is to maintain and support essential life functions such as airway and breathing.

No loss of consciousness: If an individual hits their head but never loses consciousness, it’s rarely serious. Although they might have a mild headache or a concussion, bleed from a scalp wound, or a have a large bump on their head, there is no cause for concern—unless they develop:

- A headache that progressively worsens

- Consciousness gradually deteriorates from alertness to drowsiness or disorientation. Ask the victim if they know their name, location, the date, and what happened. If they get all four correct, they are oriented x 4.

- Persistent or projectile (shoots out under pressure) vomiting

- One pupil becomes significantly larger than the other

- Bleeding from an ear or the nose without direct injury to those areas or a clear, watery fluid draining from the nose

- Bruising behind the ears or around the eyes when there is no direct injury to those areas

- Seizures

A number of materials can be substituted for commercial suture material in an austere situation. Possible suture materials include fishing and sewing nylon, the inner strands of 550 cord, dental floss, and cotton. In an absolute worst-case scenario, sutures can be made from horsehair or homemade “gut” sutures. The latter two should only be considered in an absolute worst-case scenario. If you only have improvised suture material available, you should seriously consider if suturing is the right thing to do, because anything that is organic has a much greater chance of causing tissue irritation and infection.

Staples: Staples can be used interchangeably with sutures for closing skin wounds. They are equally as effective and very easy to apply. Their main drawback is that from a cosmetic standpoint, they are inferior to sutures. They are also very expensive. They come in several sizes, ranging from 10 staples to 100.

Glue: Glue is useful for small, superficial skin lacerations; that is, lacerations of only partial thickness or just into the subcutaneous layer. When used correctly, glue provides equivalent tensile strength to sutures. It should not be used around the eyes or mouth, and it is less effective in hairy areas. There are several brands of glue available (for example, Dermabond).

Hair tying: Hair tying is not perfect but has been successfully used for scalp lacerations. The wound should be cleaned, and hair along the edges of the wound formed into bundles. Then, the opposite bundles of hair are tied across the wound to bring the edges together. After five to seven days, the hair can be cut from the wound edges.

Skull Fractures

Fracture of the skull is not life-threatening unless associated with underlying brain injury or severe bleeding. Signs of a skull fracture include a sensation that the skull is uneven when touching the scalp, blood or clear fluid draining from the ears or nose without direct trauma to those areas, and black-and-blue discoloration around the eyes (raccoon eyes) or behind the ears (Battle’s sign—a discoloration behind the ear due to injury).

Scalp Wounds

Scalp wounds are common after head injuries and tend to bleed a lot because of the scalp’s rich blood supply. Fortunately, applying direct pressure to the wound with a gloved hand can usually stop the bleeding. It might be necessary to hold pressure for up to 30 minutes.

Using a 60 to 100cc irrigation syringe, flush the area aggressively with a diluted solution of Betadine or sterilized saline solution. If you don’t have commercial sterile solutions, studies show that clean drinking water can keep a wound clean in an austere environment. Cover with a dry, sterile gauze dressing and secure with a bandage wrap. Replace the dressing at least daily; more often if possible.

4. Severe Burns

In a survival situation, burns often happen unexpectedly and have the potential to cause death, lifelong disfigurement and dysfunction. A survival approach to burn care focuses on clothing, cooling, cleaning, covering, and comforting (i.e., pain relief).

- Cool the burn to help soothe the pain. Hold the burned area under cool (not cold) running water for 10 to 15 minutes or until the pain eases. Alternatively, apply a clean towel dampened with cool tap water.

- Remove rings or other tight items from the burned area. Try to do this quickly and gently—before the area swells.

- Don’t break small blisters (no bigger than your little fingernail).If blisters break, gently clean the area with mild soap and water, apply an antibiotic ointment, and cover it with a nonstick gauze bandage. Apply moisturizer or aloe vera lotion or gel, which might provide relief in some cases.

- If needed, take an over-the-counter pain reliever, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB), naproxen sodium (Aleve), or acetaminophen (Tylenol). Aspirin products should be avoided because of platelet inhibition and the risk for bleeding.

5. Major Burns

Protect the burned person from further harm. If you can do so safely, make sure the person you’re helping is not in contact with smoldering materials or exposed to smoke or heat. With an intact EMS system, it is recommended you don’t remove burned clothing stuck to the skin. In a survival situation, use copious irrigation with a large-gauge syringe to clean the burn and remove as many embedded bits of clothing as possible.

Check for signs of circulation. Look for breathing, coughing, or movement. Begin CPR if needed. Remove jewelry, belts, and other restrictive items—especially from around burned areas and the neck.

Burned areas swell rapidly. Don’t immerse large, severe burns in cold water. Doing so could cause a serious loss of body heat (hypothermia) or a drop in blood pressure and decreased blood flow (shock). Elevate the burned area. Raise the wound above heart level, if possible.

All partial- and full-thickness burns should be covered with sterile dressings. A fine mesh gauze (e.g., Telfa) should be applied after the burn has been cleaned and a thin layer of topical antibiotic has been applied.

Recommended frequencies for dressing changes range from twice daily to once a week. Dressings should be changed whenever they become soaked with excessive exudate or other fluids. At each dressing change, the topical antibiotic should be removed as completely as possible by using gentle washings. Then, new antibiotic should be re-applied along with a new dressing.

Burns are classified based on how deeply and how severely they penetrate the skin.

First-Degree (Superficial) Burns

First-degree burns affect only the outer layer of skin (epidermis). The burn site is red, painful, dry, and has no blisters. Mild sunburn is an example. Long-term tissue damage is rare and usually consists of an increase or decrease in the skin color.

- The skin is usually red.

- Often, there is swelling.

- Pain is sometimes present.

Second-Degree (Partial- or Full-Thickness) Burns

Second-degree burns involve the epidermis and part of the dermis layer of skin. The burn site appears red and blistered and may be swollen and painful.

Partial-thickness burns:

- Possible blisters

- Involve the entire epidermis and upper layers of the dermis

- Wounds will be pink or red in color, painful, and appear to be wet

- Wound blanches when pressure is applied

- Should heal in several weeks (10 to 21 days) without grafting; scarring is usually minimal

Full-thickness burns:

- Can be red or white in appearance, but will appear dry

- Involve the destruction of the entire epidermis and most of the dermis

- Sensation can be present but diminished

- Blanching is sluggish or absent

- Will most likely need excision and skin grafting to heal

Third-Degree (Full-Thickness) Burns

- Third-degree burns destroy the epidermis and dermis and might go into the subcutaneous tissue. The burn sites may appear white or charred

- All layers of the skin are destroyed

- Extend into the subcutaneous tissues

- Areas can appear black or white and will be dry

- Can appear leathery in texture

- Will not blanch when pressure is applied

- No pain

6. Chest Trauma/Collapsed Lung

There are numerous types of possible thoracic injures one would encounter in a survival situation—from gunshot/knife wounds to falling debris and impairment. These injuries require immediate recognition and treatment. Here are some ways to recognize chest trauma:

Patients with a pneumothorax (holes in the lungs) will experience respiratory distress, including dyspnea (difficult breathing), tachypnea (rapid breathing), and tachycardia (rapid heart rate). They might also have decreased or absent breath sounds on the side of the chest with the pneumothorax. Additionally, pain with breathing is a frequent complaint.

A closed pneumothorax is associated with a trauma, either blunt or penetrating, in which the chest wall remains intact (i.e., no external wound). This is often explained by a broken rib that punctures the lung tissue. The signs and symptoms of a closed pneumothorax don’t differ much from other pneumothoraxes—that is, respiratory distress and possibly decreased or absent breath sounds on the affected side.

Chest decompression is simply releasing the air trapped within the pleural cavity. The fastest means of doing this is by needle decompression. The needle should be inserted perpendicular to the chest wall, between the second and third ribs, counting from the top) and not angled toward the mediastinum (the mass of tissues and organs separating the sternum in front and the vertebral column behind, containing the heart and its large vessels, trachea, esophagus, thymus, lymph nodes, and other structures and tissues). Avoid injuring any of the mediastinal structures. If successful (and the scene is quiet), you may hear a rush of air.

Sucking chest wound is a special type of pneumothorax. In a sucking chest wound, air is sucked into the thoracic cavity through the chest wall instead of into the lungs through the airways. This occurs because air follows the path of least resistance. The wound to the chest will normally bubble blood with breathing in and out.

How to treat:

Place an occlusive dressing on the chest wound. Treatment of a sucking chest wound includes placing an air-occlusive dressing over the site and taping it on three sides.

7. Severe Cuts and Puncture Wounds

In technical terms, deep wounds are those that cut deeper than ¼ inch beneath the surface of the skin. Because they go so far below the surface of the body, these wounds are much more likely to cause damage to a ligament, major blood vessel or artery, tendon, or an organ. The depth can also cause both internal and external bleeding. Deep wounds are most commonly cuts or puncture wounds.

Before dealing with a wound, protect yourself and the victim from blood-borne illness by putting on a set of nitrile gloves. Alternatively, you can improvise with plastic bags, a towel, etc.

How to treat:

- Direct pressure: Press on the injury with your hand and elevate above the heart. If this stops the bleeding but it starts again when you release pressure, make a pressure dressing and apply direct pressure to a pressure point.

- Upper arm/elbow wounds: Access the brachial artery, which is located on the inner side of the arm above the elbow bone between the large upper arm muscles

- Groin/thigh wounds: Find the femoral artery in the middle of the bottom crease of the groin, between the groin and the upper thigh. This is also known as the “bikini line.” This artery may require substantial pressure; press down with the entire heel of your hand to reduce circulation.

- Lower leg wounds: Press the back of the knee directly behind the kneecap to access the popliteal artery. Do not bend or move the leg to put it in a more convenient location. Reach around to the back of the leg and press up.

- Hand/foot wounds: On the inside of the wrist, move away from the thumb toward the tip of the forearm. For foot wounds, trace above the front/top of the foot right where it meets the shin. In both cases, do not forget to feel for a pulse before applying pressure. If neither of these things works, apply a tourniquet. Tighten it until the bleeding stops.

(Attitudes about tourniquets began to change in the 1990s, but the real turnaround came during the later years in Iraq and Afghanistan. The tourniquets that proved effective were commercial devices, especially the Combat Application Tourniquet (C-A-T) and SOFFT, which many studies have found to safely and effectively stop blood flow with a low incidence of adverse events.)

A tourniquet can be left in place for two hours with minimal morbidity to the effected extremity. Morbidity is unclear between two and six hours; however, more than hours in a survival situation, and the likelihood of limb loss is all but certain.

8. Shock

Shock may be caused by severe or minor trauma to the body. It usually is the result of:

- Significant loss of blood

- Heart failure

- Dehydration

- Severe and painful blows to the body

- Severe burns of the body

- Severe wound infections

- Severe allergic reactions to drugs, foods, insect stings, and snakebites

Shock stuns and weakens the body. When the normal blood flow in the body is upset, death can result. Early identification and proper treatment might save the victim’s life.

Signs/Symptoms of Shock

In a survival situation with a victim of a traumatic injury, assume that shock is present or will occur shortly. By waiting until actual signs/symptoms of shock are noticeable, you might jeopardize the victim’s life.

Examine the victim to see if they have any of the following signs/symptoms:

- Sweaty, but cool, skin (clammy skin)

- Pale skin

- Restlessness, nervousness

- Thirst

- Loss of blood (bleeding)

- Confusion (or loss of awareness)

- Faster-than-normal breathing rate

- Blotchy or bluish skin (especially around the mouth and lips)

- Nausea and/or vomiting

How to treat:

- Do not move the victim or their limbs if suspected fractures have not been splinted.

- Lay the victim on their back.

- Elevate the victim’s feet higher than the level of their heart. Use a stable object (a box, back pack, or rolled-up clothing) so their feet will not slip off.

Warning: Do not elevate legs if the victim has an unsplinted broken leg, head injury, or abdominal injury. Splint, if necessary, before elevating their feet. For a victim with an abdominal wound, place knees in an upright (flexed) position.

- Loosen clothing at the neck, waist, or wherever it might be binding.

- Prevent chilling or overheating. The key is to maintain body temperature. In cold weather, place a blanket or other like item over the victim to keep them warm and also under them to prevent chilling. However, if a tourniquet has been applied, leave it exposed (if possible). In hot weather, place the casualty in the shade and avoid excessive covering.

- Calm the victim. Throughout the entire procedure of treating and caring for a victim, you should reassure and keep them calm. Be authoritative (take charge) and show self-confidence. Assure the victim that you are there to help.

- Do not give the victim any food or drink. If you must leave the victim, or if they are unconscious, turn their head to the side—if there is no evidence of neck or back injury—to prevent them from choking should they vomit.

9. Compound Fractures

The basics of fracture manipulation are fairly straightforward. You need to correct any angulation of the bone (i.e., straighten the bone). After that, you need to pull it to length and keep it at length, if required, and then immobilize it while the bone heals (between about six to eight weeks).

The main problem is that this is extremely painful to do. In the case of a thigh bone (femur), another problem is overcoming the action of the thigh’s very strong muscles, which act to try and shorten the bone. Maintaining length on the femur will require weighed traction to overcome the muscle action for at least several weeks. The options for splinting a limb and/or establishing traction are many and varied, but the basic principles already described above are the same.

Fractures in which the bone is in multiple fragments are less likely to heal well in a survival situation without advanced medical care. In a survival situation, fractures that break through the skin (compound fractures) will almost certainly become infected. A compound fracture requires that the bone ends and wounds be thoroughly washed out. Standard fracture management principles are then applied, and high-dose antibiotics administered, if available. (A compound fracture was one of the most common causes of limb amputation prior to antiseptics and antibiotics.)

Disclaimer: Use of the information in this article is at your own risk and intended solely for self-help in times of extreme emergencies when medical help is not available and life and death is in the balance.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in the December 2015 print issue of American Survival Guide.